- Home

- Valerie Hansen

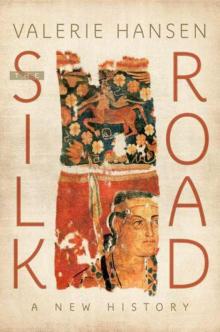

The Silk Road: A New History

The Silk Road: A New History Read online

The Silk Road

The SILK ROAD

A NEW HISTORY

Valerie Hansen

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research,

scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

©Valerie Hansen 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and

you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hansen, Valerie, 1958–

The Silk Road : a new history / Valerie Hansen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-515931-8 (hardcover : acid-free paper)

1. Silk Road—History. 2. Silk Road—History—Sources.

3. Silk Road—Description and travel. 4. Silk Road—History, Local.

5. Historic sites—Silk Road. 6. Trade routes—Asia—History. I. Title.

DS33.1.H36 2012

950.1—dc23 2011041804

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

For Jim—

who else?

Contents

Acknowledgments

Note on Scholarly Conventions

Timeline

Introduction

CHAPTER 1

At the Crossroads of Central Asia

The Kingdom of Kroraina

CHAPTER 2

Gateway to the Languages of the Silk Road

Kucha and the Caves of Kizil

CHAPTER 3

Midway Between China and Iran

Turfan

CHAPTER 4

Homeland of the Sogdians, the Silk Road Traders

Samarkand and Sogdiana

CHAPTER 5

The Cosmopolitan Terminus of the Silk Road

Historic Chang’an, Modern-day Xi’an

CHAPTER 6

The Time Capsule of Silk Road History

The Dunhuang Caves

CHAPTER 7

Entryway into Xinjiang for Buddhism and Islam

Khotan

Conclusion

The History of the Overland Routes through Central Asia

Notes

Art Credits

Index

Color plates follow page 144

Acknowledgments

This project has been a long time in the making, and many people have provided materials, answered questions, and helped in different ways. Since the first endnote to each chapter gives a detailed account of the assistance I have received, here I would like to single out those individuals whose help far surpassed the usual expectations of scholarly collegiality:

Phyllis Granoff and Koichi Shinohara, Yale University, for wise counsel about diverse Asian religious traditions usually dispensed over delicious family meals at their house;

Frantz Grenet, Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique, for imparting his knowledge of Central Asian Art and his personal collection of images, some made by the talented François Ory;

Stanley Insler, Yale University, who first encouraged me to enter this field by agreeing to teach a joint class on the Silk Road and who was always willing to answer more questions over yet another lunch at Gourmet Heaven;

Li Jian, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, who recruited me to work on a Silk Road exhibit at the Dayton Museum and introduced me to the Hejiacun finds;

Victor Mair, University of Pennsylvania, for unceasing help since he first taught me in a graduate seminar on the Dunhuang documents thirty years ago;

Boris Marshak, Hermitage Museum, who generously gave of his knowledge in conversations about and lectures on the Sogdians before his death in 2006;

Mou Fasong, East China Normal University, who hosted my family during the academic year 2005–6 and showed by example how his advisor Tang Zhangru approached his studies;

Georges-Jean Pinault, École Pratique des Hautes Études, for his guidance on Indo–European languages, particularly Tocharian;

Rong Xinjiang, Peking University, for his unrivaled knowledge of the region and willingness to lend his personal library of books and articles;

Angela Sheng, McMaster University, for her expertise on textiles and her loyal friendship;

Nicholas Sims-Williams, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, and Ursula Sims-Williams, British Library, London, who both patiently corrected multiple errors in an article I submitted to the Bulletin of the Asia Institute and for guidance on Central Asian languages, particularly Khotanese;

Prods Oktor Skjærvø, Harvard University, who has over the years answered frequent queries, traveled to Yale to give multiple presentations, and provided copies of his own unpublished translations;

Étienne de la Vaissière, École Pratique des Hautes Études, for his unfailing generosity in answering queries about all things Sogdian and many things Central Asian, often within an hour and always within a day (even in my last weeks of revising);

Wang Binghua, Renmin University, for sharing his deep knowledge of Xinjiang archeology, particularly about the sites of Niya and Loulan;

Helen Wang, British Museum, for her command of numismatics and for close readings of multiple chapters; and

Yoshida Yutaka, Faculty of Letters, Kyoto University, for his advice on Sogdian and Khotanese language and history.

Susan Ferber, my editor at Oxford University Press, has been consistently supportive since signing this book more than a decade ago, and her careful edits improved each chapter. She answered all queries with unusual alacrity, possibly because she works harder than anyone I have ever met. Joellyn Ausanka, senior production editor, oversaw the preparation of the book with extraordinary efficiency, while Ben Sadock copyedited with a gentle touch and great acuity.

The National Endowment for the Humanities provided a year of support that allowed me to study Russian and, with the help of Asel Umurzakova, immerse myself in the Mount Mugh materials. The Fulbright Scholar Program for Faculty financed my stay at East China Normal University in Shanghai, 2005–6. The Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange (USA) provided a generous subsidy for maps and illustrations.

All the Yale undergraduate and graduate students who have taken classes on the Silk Road over the years have pushed me to clarify my arguments. Elizabeth Duggan provided an insightful reading of an early draft of the introduction. The students in my Silk Road seminar in the spring

of 2010, Mary Augusta Brazelton, Wonhee Cho, Denise Foerster, Ying Jia Tan, and Christine Wight, and, in the spring of 2011, Arnaud Bertrand, read through an almost-final draft and made many valuable suggestions for revision, including starting each chapter with a document. Mathew Andrews, my research assistant, performed multiple tasks, especially the tedious preparation of images, with speed and good cheer, even as a first-year student at Yale Law School. Joseph Szaszfai and the staff of Yale’s Photo + Design unit transformed many problematic images into digital files ready for publication.

Brian Vivier, now Chinese Studies librarian at the University of Pennsylvania, carefully edited all the endnotes. Jinping Wang helped to resolve multiple last-minute queries with her characteristic erudition. Alice Thiede of Carto-Graphics drew the beautiful maps, which were particularly challenging because of all the unfamiliar place-names. Pamela Schirmeister, associate dean of the Yale Graduate School, offered an incisive critique of the introduction just days before submission.

My husband, Jim Stepanek, and our children, Bret, Claire, and Lydia, have always supported my writing and teaching with good humor. No question that the best trips have been when they, either individually or collectively, were along. The final month in China before submission was an all-out family effort to proofread, prepare charts, and polish the manuscript. What will we ever talk about now that Bret, born just before I began this project, can no longer tease me about the average number of words I wrote each day?

September 30, 2011

Beijing

Note on Scholarly Conventions

The reader will encounter multiple names from different Sanskritic, Turkic, and Iranian languages. The book gives the most commonly used spelling even if at the sacrifice of consistency. Similarly, the running text does not include diacritical marks (even when quoting sources that do), which are distracting to the general reader and already known to specialists. The notes, however, do give the diacritical marks for all authors’ names, terms, and titles of books and articles.

All Chinese names are given in pinyin, the romanization system in use throughout China. The pronunciation of several letters is not obvious to English-speakers: x, q, c, and zh are the most puzzling. The Tang monk Xuanzang (pronounced Shuen-dzahng) met the king of Gaochang, whose surname was Qu (pronounced like the French “tu”). Xuanzang’s monastery in Chang’an was called Ci’en (pronounced Tsih uhn), and the Zhang (pronounced Jahng) family ruled Dunhuang from 848 to 914.

Personal names of Westerners are given in the usual order of given name before surname, while Chinese and Japanese names follow the Asian practice of placing the family name before the given name. In the case of some scholars who publish in multiple languages, the order of given name and surname varies depending on the language of publication.

Occasionally the text quotes from sources giving quantities of certain goods. In most cases the original term is included along with a conversion to the modern equivalent, but the reader should bear in mind that, because all units of measure in the premodern world were not standardized, the modern equivalents are only approximate.

The Silk Road

RECOVERING HISTORY FROM RECYCLED PAPER

The needle marks and shape of this document indicate that it was part of a funerary garment, possibly a shirt, buried in a Turfan graveyard. The text records testimony given by an Iranian merchant before a Chinese court. This section of the document begins in the upper right-hand corner with the name of the merchant, Cao Lushan, and his age, thirty. Xinjiang Museum.

Introduction

The document on the facing page illustrates the subject of this book. It is a court record of testimony given by an Iranian merchant living in China sometime around 670 CE. The Iranian requested the court’s assistance in recovering 275 bolts of silk owed to his deceased brother. He testified that, after lending the silk to his Chinese partner, his brother disappeared in the desert on a business trip with two camels, four cattle, and a donkey, and was presumed dead. The court ruled that, as his brother’s survivor, the Iranian was entitled to the silk, but it is not clear whether the ruling was ever enforced.

This incident reveals much about the Silk Road trade. The actual volume of trade was small. In this example, just seven animals carried all of the Iranian merchant’s goods. Two were camels, but the other five were four cattle and a donkey, all important pack animals. The presence of Iranian merchants is notable, since China’s main trading partner was not Rome but Samarkand, on the eastern edge of the Iranian world. Further, the lawsuit occurred when merchants along the Silk Road were prospering because of the massive presence of Chinese troops. This court case occurred during the seventh century, when Chinese imperial spending provided a powerful stimulus to the local economy.

Most revealing of all, we know about this lawsuit because it was written on discarded government documents, which were then sold as scrap paper, and finally used by artisans to make a paper garment for the deceased. About 1,300 years later Chinese archeologists opened a tomb near Turfan and pieced together the document from the different sections of the garment. As they connected the different pieces of paper, the testimony of the different parties was revealed.

In recent decades archeologists have reassembled thousands of other documents. What has emerged are contracts, legal disputes, receipts, cargo manifests, medical prescriptions, and the poignant contract of a slave girl sold for 120 silver coins on a particular market day over one thousand years ago. The writings are in a multitude of languages including classical Chinese, Sanskrit, and other dead languages.

Many of the documents survive because paper had a high value and was not thrown out. Craftsmen also used the recycled paper to make paper shoes, statues, and other paper mache objects to accompany the dead on their journey to the afterlife. Because recycled paper documents were used to make these funeral objects, guesswork is required to piece them together. The Iranian’s affidavit, for example, was cut with scissors and then sewn to make a paper garment for the dead, leaving part of the record on the cutting room floor. Skilled historians have used the shapes of the fragments and tell-tale needle holes to reconstruct the original documents.

These documents make it possible to identify the main actors, the commodities traded, the approximate size of caravans, and the impact of trade on the localities through which goods passed. They also elucidate the broader impact of the Silk Road, particularly the religious beliefs and technologies that refugees brought with them as they sought to settle in places more peaceful than their war-torn homelands.

The communities along the Silk Road were largely agricultural rather than commercial, meaning that most people worked the land and did not engage in trade. People lived and died near where they were born. The trade that took place was mainly local and often involved exchanges of goods, rather than the use of coins. Each community, then as now, had a distinct identity. Only when wars and political unrest forced people to leave their traditional homelands did these communities along the Silk Road absorb large numbers of refugees.

These immigrants brought their religions and languages to their new homes. Buddhism, originating in India and enjoying genuine popularity in China, certainly had the most influence, but Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, and the Christian Church of the East, based in Syria, all gained followings. The people living along the Silk Road played a crucial role in transmitting, translating, and modifying these belief systems as they passed from one civilization to another. Before the coming of Islam to the region, members of these different communities proved surprisingly tolerant of each other’s beliefs. Individual rulers might choose one religion over another and strongly encourage their subjects to follow suit, yet they still permitted residents to continue their own religious practices.

Among the many contributors to Silk Road culture were the Sogdians, a people living in and around the great city of Samarkand in today’s Uzbekistan. Trade between China and Sogdiana, their homeland, peaked between 500 and 800 CE. Most of the traders named

in the excavated documents came from Samarkand or were descended from people who did. They spoke an Iranian language called Sogdian, and many observed the Zoroastrian teachings of the ancient Iranian teacher Zarathustra (ca. 1000 BCE, called Zoroaster in Greek), who taught that telling the truth was the paramount virtue. Because of the unusual conditions of preservation in Xinjiang, more information about the Sogdians and their beliefs survives in China than in their homeland.

Unlike most Silk Road books, which concentrate on art, this book is based on documents—documents that explain how things got to be where they are, who brought them there, and why Silk Road history is such a dazzling array of peoples, languages, and cultural cross-currents.

Not all documents discovered along the Silk Road from 200 to 1000 CE (the main focus of this book) were on recycled scrap paper. Some were written on wood, silk, leather, and other materials. They were recovered not only from tombs but also from abandoned postal stations, shrines, and homes, and beneath the dry desert—the perfect environment for the preservation of documents as well as art, clothing, ancient religious texts, ossified food, and human remains (see color plate 1).

These documents are unique because many were lost, found by accident, and written by people from a wide swath of society, not only the literate rich and powerful. These documents were not consciously composed histories: their authors did not expect later generations to read them, and they were certainly never intended to survive. They offer a glimpse into the past that is often refreshingly personal, factual, anecdotal, and random. Nothing is more valuable than information extracted from trash, because no one has edited it in any way.

Most of what we have learned from these documents debunks the prevailing view of the Silk Road, in the sense that the “road” was not an actual “road” but a stretch of shifting, unmarked paths across massive expanses of deserts and mountains. In fact, the quantity of cargo transported along these treacherous routes was small. Yet the Silk Road did actually transform cultures both east and west. Using the documentary evidence uncovered in the past two hundred years and especially the startling new finds unearthed in recent decades, this book will attempt to explain how this modest non-road became one of the most transformative super highways in human history—one that transmitted ideas, technologies, and artistic motifs, not simply trade goods.

Military K-9 Unit Christmas: Christmas Escape ; Yuletide Target

Military K-9 Unit Christmas: Christmas Escape ; Yuletide Target Marked For Revenge (Emergency Responders Book 2)

Marked For Revenge (Emergency Responders Book 2) Canyon Standoff

Canyon Standoff Trail of Danger

Trail of Danger A Puppy's Tale

A Puppy's Tale Marked for Revenge

Marked for Revenge Fatal Threat

Fatal Threat Christmas Vendetta

Christmas Vendetta Dangerous Legacy

Dangerous Legacy Blessings of the Heart

Blessings of the Heart Montana Reunion

Montana Reunion Her Montana Cowboy

Her Montana Cowboy Wilderness Courtship

Wilderness Courtship Rookie K-9 Unit Christmas

Rookie K-9 Unit Christmas Rescuing the Heiress

Rescuing the Heiress The Danger Within

The Danger Within Family in Hiding

Family in Hiding Love Inspired December 2013 - Bundle 2 of 2: Cozy ChristmasHer Holiday HeroJingle Bell Romance

Love Inspired December 2013 - Bundle 2 of 2: Cozy ChristmasHer Holiday HeroJingle Bell Romance The Silk Road: A New History

The Silk Road: A New History Search and Rescue

Search and Rescue Standing Guard

Standing Guard Small Town Justice

Small Town Justice Explosive Secrets (Texas K-9 Unit)

Explosive Secrets (Texas K-9 Unit) Threat of Darkness

Threat of Darkness Bound by Duty

Bound by Duty The Hamilton Heir

The Hamilton Heir Face of Danger

Face of Danger The Troublesome Angel

The Troublesome Angel Healing the Boss’s Heart

Healing the Boss’s Heart Deadly Payoff

Deadly Payoff Samantha's Gift

Samantha's Gift Her Cherokee Groom

Her Cherokee Groom Everlasting Love

Everlasting Love The Perfect Couple

The Perfect Couple Blessings of the Heart and Samantha's Gift

Blessings of the Heart and Samantha's Gift Nightwatch

Nightwatch Nowhere to Run

Nowhere to Run The Doctor's Newfound Family

The Doctor's Newfound Family The Rookie's Assignment

The Rookie's Assignment Frontier Courtship

Frontier Courtship Out of the Depths

Out of the Depths Special Agent

Special Agent Hidden in the Wall

Hidden in the Wall